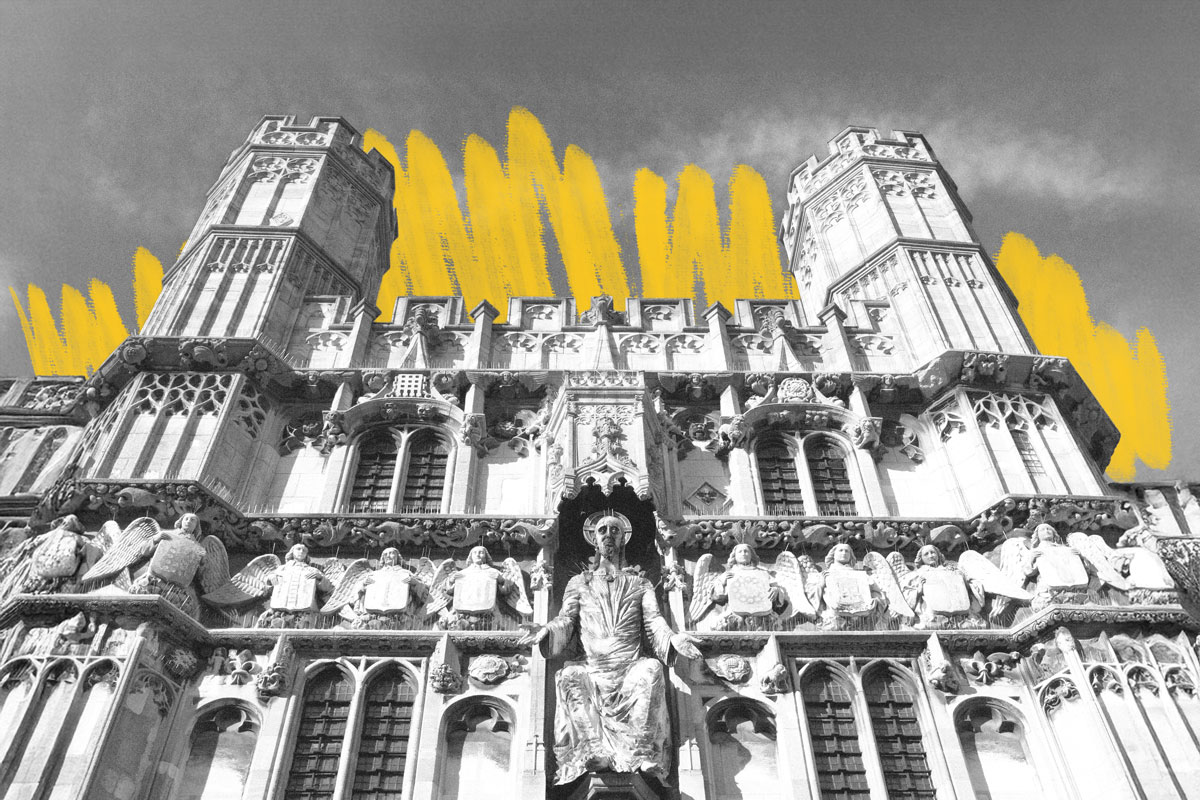

Medieval cathedrals were painted in vibrant colors — not gray stone. |

World History |

|

| |

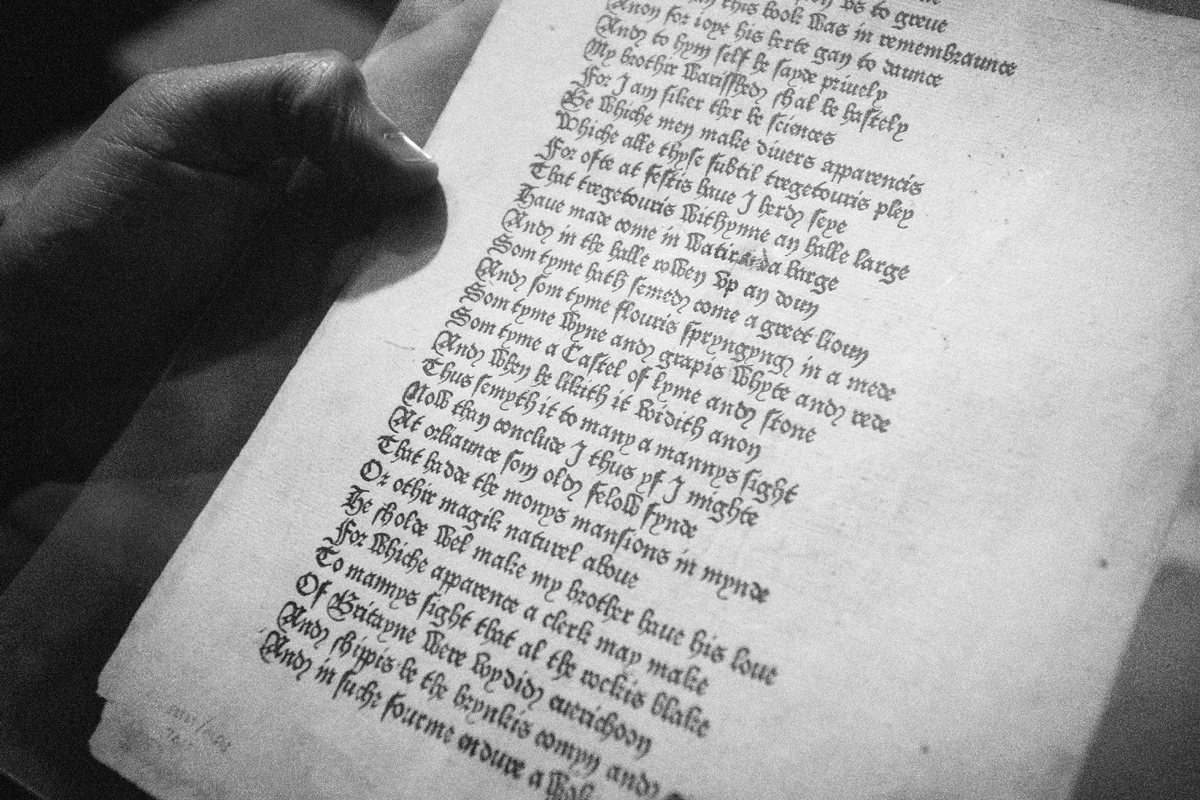

Recent studies have made it clear that medieval churches were originally covered in vibrant pigments: reds, blues, ochres, greens, and gold. Exterior sculptures were painted to resemble living figures, while interiors were layered with murals, patterned columns, and richly colored vaults. Traces of this polychromy (the use of many colors) still survive at sites such as the Gothic cathedrals in Amiens and Chartres, and scientific analysis has confirmed pigment residues on cathedrals across Europe. | |

So why do these structures look so colorless now? Time played a role, as weathering, oxidation, and pollution gradually stripped paint from stone. But later human choices mattered even more. During the Reformation (the religious revolution of the 16th century), murals were deliberately painted over to fit new ideals. In the 18th and 19th centuries, restorers scraped paint from statues and walls to match modern tastes that prized "pure" stone. These decisions reshaped how the Middle Ages would be remembered. | |

Yet that preference for monochrome was never medieval. As historian Yvonne Seale has noted, medieval people thought about color differently than we do, and primarily in terms of expressions of clarity, brilliance, and spiritual "greatness." Bold, saturated colors carried meaning. The deep blues used for the Virgin Mary's cloak, for example, were meant to soak the senses and signal holiness. | |

Seen this way, gray stone cathedrals aren't timeless relics — they're artifacts of later centuries. The medieval world was anything but dull. Its churches were designed to dazzle, instruct, and envelop visitors in color, light, and meaning, from painted façades to stained glass that quite literally bathed worshippers in sacred hues. |

| |||

| |||

What Happens Without an Estate Plan | |||

Planning your estate may not sound exciting, but it plays a significant role in protecting what you've built. The Investor's Guide to Estate Planning makes the process more approachable, with straightforward guidance on key documents that clarify your wishes and perspective on family conversations and financial legacy. | |||

*This content is brought to you by our sponsor, which helps keep our content free. |

| |||||||||

By the Numbers | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

The Gothic style largely began with a French abbot's vision. | |||||||||

The Gothic cathedral did not simply evolve: It was championed by one powerful individual. Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, near Paris, played a central role in shaping the new style in the early 12th century. As abbot of Saint-Denis — the burial church of French kings and a center of royal authority — Suger oversaw a dramatic rebuilding of the abbey's eastern end in the 1140s. Using pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and innovative structural systems, he replaced heavy Romanesque walls with soaring spaces filled with stained glass. For Suger, light was not decorative but theological. He believed brilliance and color could draw worshippers' minds upward, toward the divine. This vision mattered especially in cathedrals — churches that housed a bishop's cathedra, or throne. In the Middle Ages, such buildings were known as ecclesia cathedralis, "churches of the throne," and served as centers of spiritual authority. (Eventually the term was shortened to simply "cathedral.") Suger's glowing Saint-Denis abbey became a model for later cathedrals across France and England, demonstrating that architecture itself could teach, inspire, and embody sacred power. | |||||||||

| |||

Recommended Reading | |||

| |||

Science & Industry | |||

| |||

| |||

Arts & Culture | |||

| |||

| + Load more | |||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||

| 325 North LaSalle Street, Suite 200, Chicago, IL 60654 | |||||||||

|

Ni komentarjev:

Objavite komentar